Today we share guidance on creating a well structured competency framework. Covering topics such as what to include, choosing the correct level of detail and defining target levels.

In a previous post we discussed why it’s important to have a competency framework. In this article we'll be going into more details on how to establish the structure of your competency framework. Think Eleven have worked closely with many organisations over the last 15 years, and this post covers industry best practice, regardless of your organisation’s size or sector.

Structure is Important

Different organisations have their own reasons for structuring a competency framework. These may include:

- Preparing to use new software or systems for managing competence

- Streamlining or reducing noise in data that has accumulated over a long period, often with many different managers applying different approaches

- To allow appraisals to be conducted that use objective metrics and targets

- To plan and prepare for a restructure

The overall goal is to produce a framework that is immediately recognisable to all areas of the organisation, is understandable and easy to adhere to, and can be reported upon.

Before you start - gather the subject matter experts!

One of the biggest mistakes organisations make is to develop competency frameworks in isolation. It is critical that subject matter experts from around the organisation are invited to participate in its creation. In addition to ensuring that all subject areas get covered in appropriate detail, it will also encourage buy-in and support when its time to introduce your competency framework into the organisation.

What to include in your competency framework?

The core aspect of a competency framework are the skills and proficiencies that reside within it. Different organisations have different requirements, and these may be influenced by the industry sector, clients, or even legislation. You should aim to include the following:

Generic skills

Skills that are common across either all people, or large groups of people. Examples include the company induction and company policies.

Hard skills

These are the essential skills that determine a person’s ability to complete their role / responsibilities in a competent, unsupervised manner.

Peripheral skills

These aren’t directly related to roles or responsibilities, but may be important in certain circumstances, for example, First Aid.

Soft skills

These relate more closely to how a person works. For example, listening skills, time management, and creativity. They often can be related to attitude & behaviours or the core values of a person.

Descriptions

Descriptions are important to clearly distinguish the purpose of each skill to the organisation. This information may also include aims, objectives, outputs or goals.

Target Levels

Specify target levels for each skill against each person/role it is applicable to. Also, ensure that your targets are clearly defined with no ambiguity. We’ll look at examples of how to do this effectively in a later post.

Choosing the correct level of detail

Your skills should be based on the lowest denomination that requires management and reporting. For example, a particular process may be broken down into many smaller tasks, with each task vital to the overall process. In this case, each task should be listed in the framework with its own metrics and supporting information.

For example, this title may be too generic:

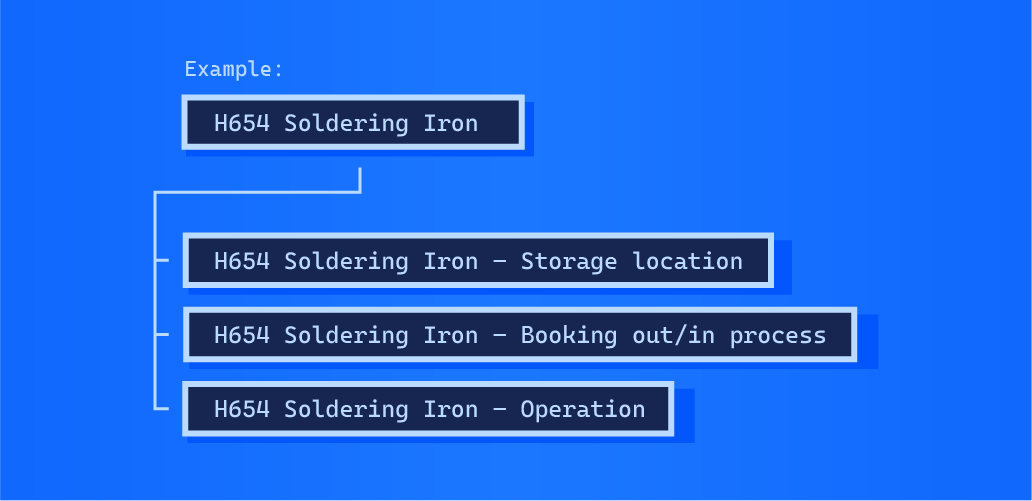

There may be multiple processes for the safe and competent operation of this device. Therefore, this title might need to be broken down into its constituent parts with respective aims & objectives, where each can be trained, managed and reported on appropriately:

There are no rules about how to group/list skills – this decision should be made by your subject matter experts or steering committee. For example, you may group skills by task, process, machine or area.

Meaningful skills titles with supporting context

This is vital if you are developing your framework to be migrated into a software system, or for reporting purposes. Aim to use short, concise titles, but include supporting information at a lower level to provide clarity to people with lesser experience or knowledge.

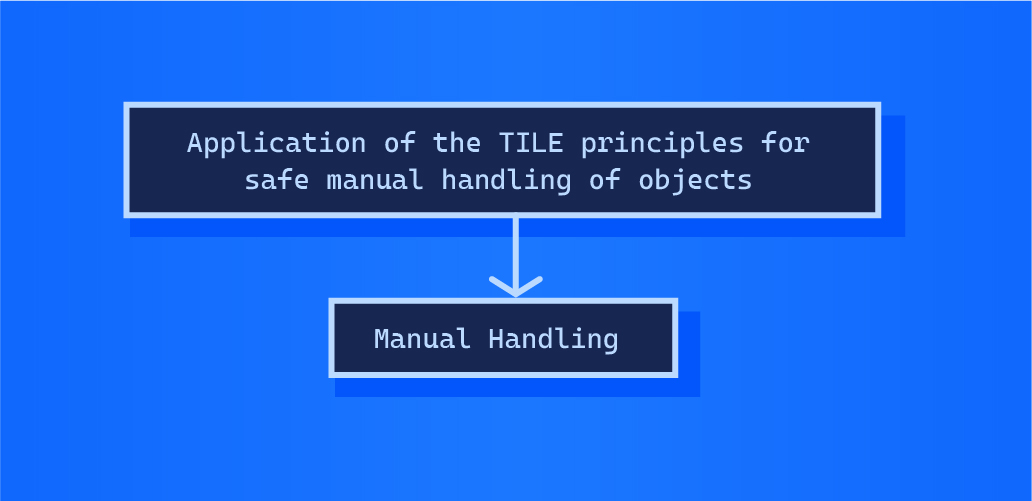

This is an example of a poor skill title:

Application of the TILE principles for safe manual handling of objects

This is not concise and confuses the title with a description. Titles and descriptions should be separated to ensure that reporting is clear and concise, while additional and contextual information is there if needed. A more appropriate title could simply be:

Manual Handling

Aims and objectives, outcomes and any additional supporting information can then be defined separately.

Separate skills from job roles

When defining the list of skills for the competency framework, avoid categorisation by job titles unless necessary. This is because many job roles may share common skills, such as:

Company Induction or Production - Health & Safety Induction

This can create a huge amount of duplication in the framework. However, an exception to this is where a similarly named skill is used in a different context in a different area of the business. Take for example:

Microsoft Excel

Your colleagues within Human Resources will use Microsoft Excel in a completely different manner to those in Engineering or Quality. This does not imply that any level of proficiency is “better” or “more respectable”. Therefore, it may be better to create alternative titles with their own objectives that make the context clearer, for example:

Microsoft Excel – Generic functionality for all

Microsoft Excel for Engineers

Microsoft Excel for Senior Engineers

Microsoft Excel for Human Resources

The target levels and outcomes for the above can therefore be meaningful to their respective context. Alternatively, as mentioned already, if specific functionality is required in the organisation, then structure the titles appropriately, e.g.

Microsoft Excel – Pivot Tables

Microsoft Excel – Conditional Formatting

Identifying Duplication

Another good reason for including subject matter experts will be their ability to highlight and standardise duplication. Competency frameworks often contain many different skills that all relate to the same underlying thing, for example:

Manual Handling

Safe Lifting

Movement of Heavy Objects in the Workplace

Unless the context or application is different (which should become apparent from each one’s supporting description), they can be combined and harmonised.

Defining subject matter expert skills

Chemical Awareness for example may require a higher level of proficiency for certain roles in the organisation, such as the Health & Safety Manager, who must be both an expert in the context of his own role, as well as a trainer for other staff.

This may be represented by a target level that is higher for that respective job role, or a separate skill may be created to further highlight the expert nature: Chemical Awareness – Expert/Trainer

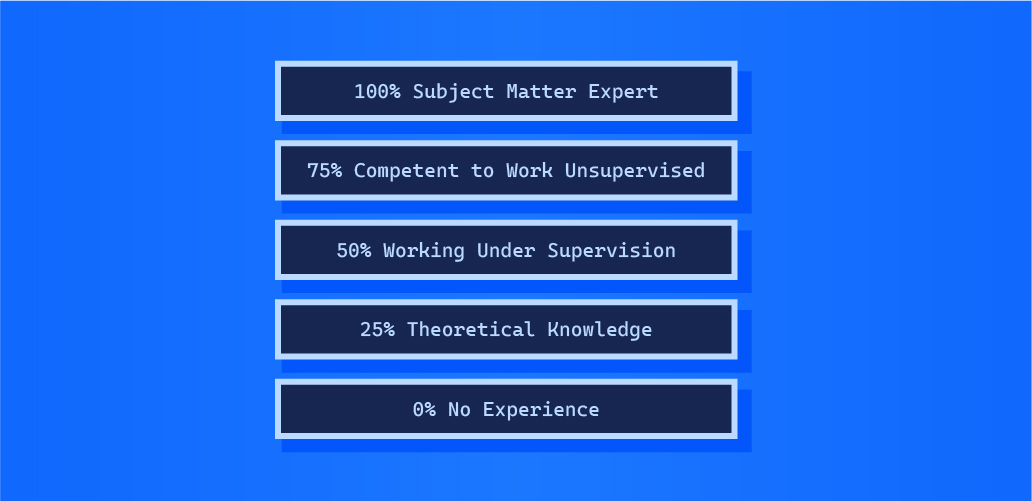

Defining target and competency levels

It is important to select levels of proficiency that are standardised across the organisation, and meaningful. Percentage levels are generally the best option because they allow powerful reporting with averages to be easily achieved. It is important that levels are also given a description, but this is something we'll cover in more detail in a future post.

Aim for a single and standard approach for the whole framework e.g., percentage levels rather than mixing level 1-10 plus ILU, as wider-scale reporting and analysis becomes virtually impossible.

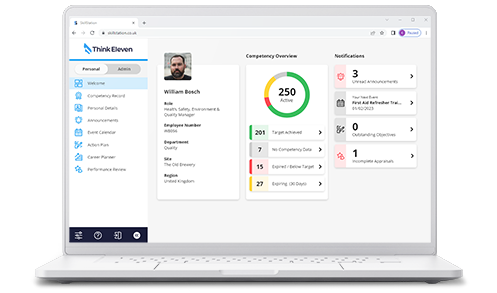

Linking skills to people

Once your framework skills are defined, you will need to associate them to the respective people. There are no rules on how this should be done, but you may link skills to job roles, responsibilities, geographical areas or directly to individuals.

Deploying your competency framework

Make sure that your framework is communicated to the organisation with all the benefits that it will bring. You may encounter cultural barriers and resistance to change, but standardisation and clearly defined outcomes will improve your organisation in every way.